The thyroid gland can store these hormones for later use and release them when needed. Once released, the hormones travel through the bloodstream to target cells.

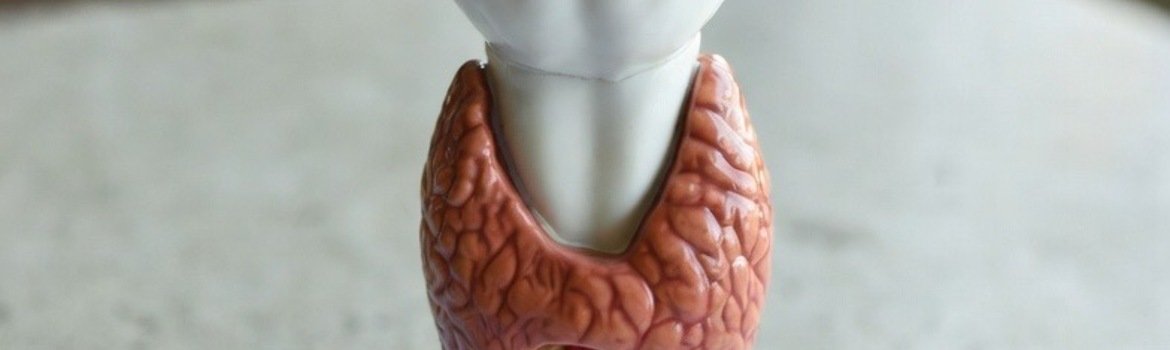

As mentioned earlier, the thyroid gland is located at the front of the neck, in front of the trachea. Upon closer examination, the thyroid gland appears reddish-brown in color. This coloration is due to its rich blood supply and extensive innervation. Blood is supplied to the thyroid through the superior and inferior thyroid arteries, which branch from the external carotid artery. Structurally, the gland consists of two lobes connected by a central bridge known as the isthmus.

The location of the thyroid gland is relatively easy to visualize, as it is routinely examined during medical check-ups. A normal-sized thyroid gland is usually not palpable and becomes noticeable only when it is enlarged or when nodules develop.

The thyroid gland plays a central role in regulating the body’s metabolism. Metabolism can be defined as the body’s ability to convert food into energy. In addition, the thyroid gland secretes hormones that regulate vital bodily functions and help maintain internal homeostasis. Among the fundamental physiological processes influenced by thyroid hormones are breathing and heart rate.

Body weight is also influenced by thyroid function, which explains why individuals with thyroid disorders may experience significant weight fluctuations. Furthermore, thyroid hormones help regulate internal body temperature and cholesterol levels.

The lobes of the thyroid gland are responsible for synthesizing thyroid hormones. These hormones exert widespread effects, influencing nearly every tissue in the body through endocrine signaling. At the cellular level, thyroid hormones increase metabolic activity and stimulate protein synthesis, which is essential for normal growth and development.

The main thyroid disorders include:

Hyperthyroidism (excessive hormone production)

Hypothyroidism (insufficient hormone production)

Goiter

Thyroid nodules

Thyroid cancer

A person’s risk of developing thyroid cancer depends on several factors, including age, sex, non-cancerous thyroid conditions, and family history. The presence of one or more risk factors does not guarantee the development of thyroid cancer.

Age and sex. Thyroid cancer occurs more frequently in women than in men, particularly during reproductive years. Most women diagnosed with thyroid cancer are between 44 and 49 years of age, whereas men are more often diagnosed at an older age, typically between 80 and 84 years. The exact causes of thyroid cancer remain unclear, and researchers continue to investigate possible associations with pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, menopause, and aging.

Obesity. Individuals who are overweight or obese have a higher risk of developing thyroid cancer.

Benign thyroid conditions. Certain non-cancerous thyroid diseases, such as goiter, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and thyroid adenomas, are associated with an increased risk of thyroid cancer. Although thyroid nodules are common, only about 5% are malignant.

Family history. Individuals with a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) who has had thyroid cancer have an increased risk compared to the general population. However, thyroid cancer remains relatively rare.

Radiation exposure. The thyroid gland is highly sensitive to radiation. Individuals exposed to radiation, particularly during childhood, may develop thyroid nodules years later. While most nodules are benign, medical evaluation is essential. Increased rates of thyroid cancer have been observed in populations exposed to nuclear accidents, such as after the Chernobyl disaster, particularly among children and adolescents. Iodine deficiency further increases the risk following radiation exposure.

Systemic lupus erythematosus. Studies indicate that individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus have approximately twice the risk of developing thyroid cancer compared to the general population.

Thyroid cancer is relatively rare compared to other cancers. In 2021, approximately 44,000 new cases were diagnosed in the United States, compared with over 280,000 cases of breast cancer and more than 150,000 cases of colorectal cancer. Despite its generally favorable prognosis, around 2,000 deaths from thyroid cancer occur annually. In 2018, nearly 900,000 individuals in the United States were living with thyroid cancer.

Most cases are highly treatable, often cured through surgery and radioactive iodine therapy. Even in advanced stages, the most common types of thyroid cancer respond well to treatment. Although a cancer diagnosis can be distressing, patients with papillary and follicular thyroid cancer typically have an excellent prognosis.

Papillary thyroid cancer accounts for approximately 70–80% of all cases. It grows slowly and frequently spreads to cervical lymph nodes but generally has an excellent prognosis.

Follicular thyroid cancer represents about 10–15% of cases and may spread through the bloodstream to distant organs such as the lungs and bones. Papillary and follicular cancers are collectively known as well-differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC).

Medullary thyroid cancer accounts for roughly 2% of cases. Genetic testing for RET proto-oncogene mutations can enable early diagnosis in affected families. Approximately 75% of cases are sporadic rather than hereditary.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is the most aggressive and least responsive to treatment. It is rare, accounting for fewer than 2% of thyroid cancer cases.

Thyroid cancer often presents as a single nodule or multiple nodules in the thyroid gland and typically causes no additional symptoms. Blood tests, including thyroid hormone levels, are usually normal. Thyroid nodules are often discovered incidentally during imaging studies such as CT scans or ultrasounds performed for unrelated reasons.

In rare cases, symptoms may include neck, jaw, or ear pain. Large nodules may compress the trachea or esophagus, causing difficulty breathing or swallowing, or a sensation of throat irritation. Hoarseness may occur if the cancer affects the nerve controlling the vocal cords.

If thyroid cancer is suspected during physical examination or ultrasound, a biopsy is performed. Definitive diagnosis is typically made after surgical removal of the nodule. Although thyroid nodules are common, fewer than 10% are malignant.

Surgery is the primary treatment for all types of thyroid cancer. Depending on tumor size and spread, treatment may involve lobectomy or total thyroidectomy. If lymph node metastases are present, affected lymph nodes may also be removed. Small papillary microcarcinomas (<1 cm) may be safely monitored without immediate surgery in selected cases.

Patients who undergo total thyroidectomy require lifelong thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Surgery alone is often curative, especially for small tumors. In higher-risk cases, radioactive iodine therapy may be used to eliminate remaining thyroid tissue or cancer cells.

The prognosis for differentiated thyroid cancer is excellent, particularly in patients younger than 55 years with localized disease. While recurrence risk increases with age and tumor aggressiveness, long-term survival remains high. Lifelong follow-up is recommended for all patients.